The book is called, appropriately, Comics Art, and published by Tate (the art gallery people, so it really is about art). The thing about this book is that you will hardly find any American Marvel or DC superheroes within its covers. And if you think that is all there is to comics, you're in for a big surprise. Even if you know Raymond Briggs, Hergé, Art Spiegelman and Marjene Satrapi as comics authors and artists you'll find a treasure trove of other gems herein.

Did you know, for example, that it took a panel of experts many days to decide together when the first comic was produced? The occasion was a comics festival in Italy in 1989, and the panel decided upon an issue of a newspaper strip from Sunday, 25 October 1896 in the New York Journal called The Yellow Kid, because, amongst its characteristics, was the first use of speech balloons, together with a series of linear 'panels'.

This is a shame, because I thought I owned an earlier 'graphic novel', an English translation of Mr Oldbuck's Adventures, dating from around the 1880s, but in this instance there are no word balloons, just pictures with a caption beneath them telling the story.

The book examines all the different ways in which artists have been and are continuing, particularly nowadays, to stretch the possibilities of a medium that has really come of age: trying to use visual imagery instead of language to convey emotions such as Lighter Than My Shadow by Katie Green, about bulemia, messing around with associations, as with Seth's George Sprott, or playing around with the subjectivity of time passing, as with Pebble Island by Jon McNaught.

Paul is especially astute when analysing the political aspects, whether intended or not, of comics. For example, in a discussion of stereotypes in comics, he looks at ways in which comics have been used both to promote and to subvert stereotypical prejudices.

Paul is especially astute when analysing the political aspects, whether intended or not, of comics. For example, in a discussion of stereotypes in comics, he looks at ways in which comics have been used both to promote and to subvert stereotypical prejudices.Perhaps the most courageous example of this is by Gene Yang, who challenged the offensive image of the buck-toothed Chinese stereotype and turned it to positive use as Cousin Chin-Kee, a satire of "the worst racist prejudice".

Paul looks at graphic reportage such as Ukrainian Notebooks by the Italian artist Igort, who spent months in that country unearthing stories about the famine engineered in 1932-3 by Stalin to enforce his farming collectivisation programme in which tens of thousands died. No wonder many Ukrainians now do not want to be part of Russia.

There has also been a massive trend recently for autobiography in comics which some feel has been overdone and itself has been subverted by a spoof autobiography (Momon by Thomas Boivin et al. masquerading under the name Judith Forest).

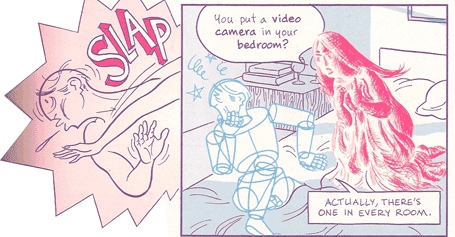

Artists are still extending the vocabulary of comics. One of my favourite examples which Paul quotes is Asterios Polyp by David Mazzuchelli, who not only introduces different typography and balloon shapes for different characters but messes around with different artistic styles for the characters at times in order to give further expression to their different points of view. Further, he deliberately limits his palate to blue and red (and their combinations) to enforce his creativity.

You can read Comics Art just by looking at the pictures and obtain a fantastic overview of the sheer creative possibilities of comics for telling stories of every particular kind.

Comics are not a genre, they are a medium like the novel or the film, and every conceivable type of genre has been tried within the medium. They are peculiarly subjective, just like reading a book, but reaching out to more senses and more associations in the mind of the reader.

I first met Paul when we worked together on a magazine with the unfortunate name of Pssst! back in the early 80s: we were both on the editorial committee and I was a contributor. Later, with his and Peter Stanbury's Escape imprint, he published some of my stories. Meanwhile he was amassing the most extensive library of graphic novels I have ever seen.

God knows how many he has now, but he has curated many shows and knows everybody who is anybody in the medium and industry, yet remains forever modest. This is a truly informative, inspiring and intelligent book.

No comments:

Post a Comment